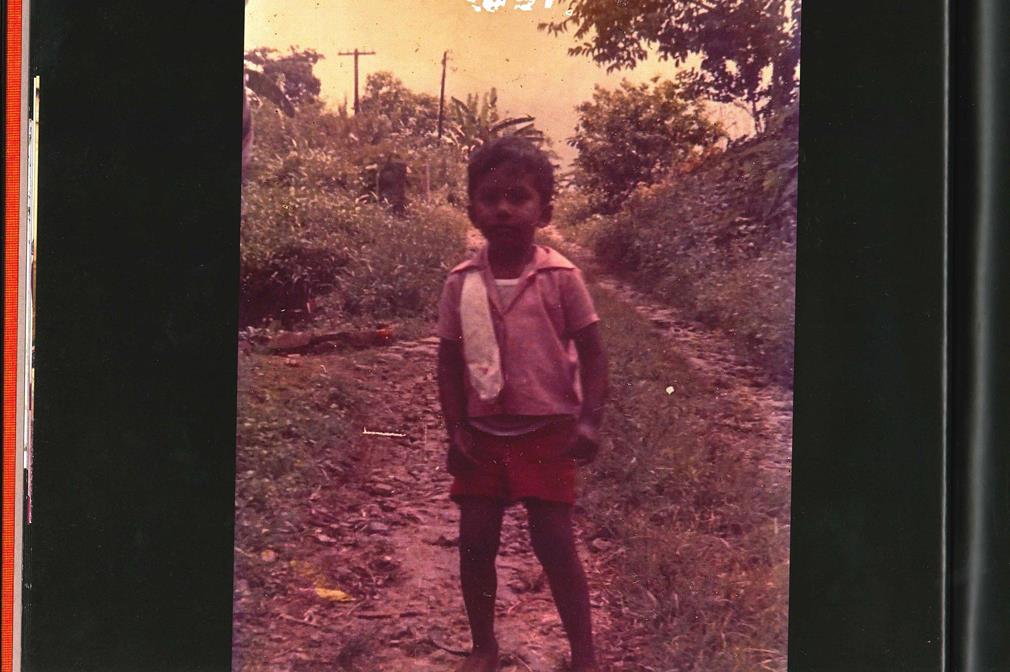

I grew up in Sri Lanka during the ethnic conflict. It lasted for the first 30 years of my life. My mother is Sinhalese and my father is Tamil, which is a bit like having a Protestant father and a Catholic mother in Belfast. It was an unusual situation, but it did help us see all sides of the conflict.

During the anti-Tamil riots of 1983 our house was attacked and my family had to go into hiding. Then during the Marxist uprisings of 1987-89 I remember not going to school for a long while. When I was fifteen I heard what I thought was the school gate collapsing, but it turned out to be an LTTE (aka Tamil Tigers) bomb at the central bank that killed almost a 100 people. I saw first-hand the consequences of bigotry, injustice and violence.

I was angry, but felt helpless, because I did not really know how to address any of these issues.

I was involved in student activism but did not see those efforts go anywhere. Then one day, shortly after finishing my secondary school exams, I attended a lecture by a constitutional scholar in Sri Lanka. He described how the law could have a massive impact on the lives of ordinary people by either preventing or allowing abuses of power. This notion of the law as a tool, something that you could use to protect vulnerable people, was life-changing for me. It helped me channel my energy. It gave me a weapon with which to fight back against mass violations of human rights.

My name is Pubudu and I am a trial lawyer in the ICC's Office of the Prosecutor.

In essence, a trial lawyer goes to court and litigates cases. But there is a lot of preparation that goes with that – including interviewing witnesses together with investigators, reading witness statements, studying other evidence together with analysts, drafting motions, and deciding on the exact contours of the charges. Afterwards, during the trial, we question witnesses in Court, cross-examine Defence witnesses and address the challenges brought by the Defence.

Studying patterns

When you are assigned to a preliminary examination or an early investigation, you start with an open mind and very steep learning curve. You don't have a large evidence collection, you haven't interviewed many witnesses. So you study what kind of crimes have occurred, what kind of victims there are, and the groups involved. Was there a campaign of sexual violence? Was any set of victims targeted because of their ethnicity, or gender or some other aspect of their identity? Did any group conscript and use children under the age of 15? Who were the key actors in these groups?

You seek out patterns of criminality that happen in a country... and aim to answer two main questions: 1. What are the crimes that were committed here? 2. Who are the persons most responsible for these crimes?

Then, over time, we keep refining the answers to those questions, collecting evidence, analysing, asking more questions and collecting more evidence until, we know enough to get an arrest warrant against someone, and then bring them to Court to start proceedings against them.

It's important to remember at this point that the accused is presumed innocent until proved guilty, and the Prosecution has the burden of proving the guilt of the accused.

Determining the charges

We then need make a decision on what charges to bring against this person.

You have to make the charges sufficiently clear and precise so that the accused has a reasonable ability to understand and challenge the case against him or her. You have to make sure that your case is broad enough to reflect the suffering of the victims. But you have to focus the charges and your case enough so it doesn't take five or ten years to run the trial.

Once you've decided on the charges, there is a hearing to confirm the charges. At this hearing, an ICC Chamber decides whether or not there is sufficient evidence to confirm the charges and commit the case to trial.

If a case goes to trial, part of my role as a trial lawyer for the Prosecution is to examine witnesses called by the Prosecution, and later those called by the Representatives of Victims, and the Defence. We gather and disclose both incriminating and exonerating evidence in order to establish the truth.

At the end of the trial, together with my team, I study all the evidence elicited during the trial. We use the evidence to weave together a clear description of events. We use the various pieces of evidence like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, to understand the truth of what happened. We then present this account, summarizing the evidence, to the Trial Chamber in the form of a long document: the closing brief. The lawyers for the Defence and the Victims do the same.

The Trial Chamber then studies the evidence. If the Chamber is convinced of the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt, then the Chamber convicts the accused. If not, the accused is acquitted.

Diverse environments

As a trial lawyer, you get to work in a number of very different environments.

Our offices are just like any other offices, little cubicles, without much character. Mine is covered in whiteboards, because I like to sketch out ideas.

On the other hand, the courtroom is a very intense environment. When you're on your feet, making submissions, or examining a witness, your senses are heightened; your adrenalin is pumping.

For someone who has not been in a courtroom before (and that's true for most witnesses!), a courtroom is a strange environment: people talk in a formal, almost artificial way, often using a lectern. They are dressed in black and blue robes. There are computers everywhere. There are interpreters looking down at you from their booths above.

Sometimes I travel to meet and interview witnesses. This is usually more of an investigator's job, but sometimes, for certain witnesses, trial lawyers participate in interviews as well. Here we encounter another, entirely different, environment.

Usually, we meet and interview witnesses in places that are very different from the seat of the Court. In The Hague, it's easy to get from place to place. It's easy to find a safe place to talk to people. There are no major safety or security concerns. It's a little bubble of predictability. This is not true for many of the places where we interview witnesses and collect other evidence. It may be a place where there is ongoing conflict nearby, or a place that is still recovering from a recently ended conflict. You may have trouble reaching witnesses. You have to be very careful to make sure that you don't endanger witnesses in any way. You also have to watch out for the safety and security of your own team. You have to work effectively with local authorities and intermediaries while maintaining your independence.

When talking to a witness, first contact is key. It is a vital part of building a relationship of mutual trust.

Many witnesses have undergone traumatic experiences. Their current lives may still be difficult. Meeting you might be a significant disruption to their lives. They may be fearful about their safety. Talking about their experiences may be traumatic as well. So it is vital that you approach witnesses with empathy, respect and an open mind.

Other challenges

The unique challenges faced by the ICC do not end in the field; you can also see them as they unfold in the Courtroom. Language, for example. It may be that the accused speaks a language that doesn't have a standard written form. In ICC proceedings, you need to disclose to the accused the evidence you are going to rely on, in the language of the accused. So how do you give the accused a statement if her or his language is not a written one? Similarly, how do you question a witness if there are no interpreters who speak both the language of the witness, and a working language of the court?

Then there are the types of crimes we are dealing with. How do you prove a campaign of criminality that took place over an area covering many towns and villages, over many weeks and months? How do you explore any link that may exist between a crime committed by a foot soldier, and a commander several levels up in the hierarchy? How do you establish whether a particular mass grave was related to an attack that you are investigating? How do you investigate the activities of a group or government, if it is still active or in power, and is trying to intimidate witnesses? How do you investigate a crime if you have no access to the crime scene? These are all challenges with which we grapple.

What keeps me going

The people I meet in this job keep me going. When I talk to witnesses and they speak of what they went through, it drives me to work harder and gives my work meaning and purpose. The experiences they share make me more conscientious about how I do my job. Their stories stay with me for years, sometimes more than a decade after I last met them.

In one case, there was a witness I met who was not much older than me, who was a tremendously bright, personable man. When we met, we got along well. I couldn't help comparing my life with his. I had had so much more opportunity. I went to school, I went to university. He didn't get any of those chances and had to drop out of school early in life. Much of his life was ruined because of the war in his country. At that time, I thought, what a terrible, terrible waste. Here is this man who, in any other situation, would have excelled at anything he wanted to do. And maybe we would have been friends, in a different world. And it troubled me that he was restarting his life after losing so much time. There was an element of hope, of course, because at least he could restart now. But then you think: What if the last 25 years had not been lost; wasted by war? That question motivated me to help him talk.

I have had many encounters like this. A severely injured witness who was reluctant to even take a break during an interview because they were so motivated about telling you their story; A young woman struggling to recount the trauma of sexual violence. I hope that the experience of testifying will provide them with some measure of closure. It's their stories, not mine, that matter.