Trauma, healing and hope in northern Uganda

With Martin Dennis Okwir

It was a cloudy Thursday morning in October 2017, when we arrived at Te-Okutu village for an ICC outreach meeting in Lukodi, Gulu district. Lukodi is a site listed in the charges against Dominic Ongwen, who is now on trial before the ICC.

At Te-Okutu we were received by a buzzing sound of local music on the speakers hired for the community meeting. Local tunes are commonplace in gatherings across the region. They sometimes recount the heinous experiences brought by the past conflict in northern Uganda, but also the people’s hope for a peaceful future.

In Acholi, it is believed that songs are a valuable tool for communication, but also a form of psychotherapy. Music is also used as an instrument of mobilization. To the rhythm of this music, the community members quickly trickled in and the meeting simply eased into session.

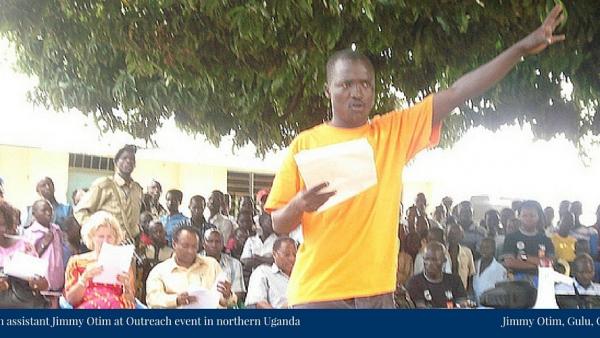

On this day, our Outreach team was on a joint mission of the Office of Public Counsel for Victims, the Legal Representative of Victims, and the Registry, to meet victims participating in the Dominic Ongwen trial. The people of northern Uganda live in the aftermath of over two decades of violence. Whenever they are gathered, it is very easy to see the heavy burden of the conflict on the collective soul of the community. The people of Acholi are generally a jolly lot, but even in their smiles, one can easily see the individual suffering and the community pain just a layer beneath. Things that atrocities of war can do to a people! Well, Te-Okutu was no exception.

“Even in their smiles, there is pain just a layer beneath”

Continuing the legacy of earlier organisations that provided psychosocial support to children returning from captivity, a host of organisations supported by the Trust Fund for Victims (TFV) are spread all across the region to address the community’s psychosocial needs. A closer look, however, reveals that trauma still constitutes a serious and widespread problem across the post-conflict communities of northern Uganda. The effects of this span far beyond the afflicted individuals and in many ways results in a serious breakdown of how families function, both socially and economically.

We at the Court’s Outreach team in Uganda recognise how trauma interplays with some of our community engagements. When we screen videos of the Dominic Ongwen trial to affected communities in northern Uganda, we incorporate the services of locally available partner organisations that provide psychosocial services to communities to be on site and help attend to any counselling needs that may arise as a result of the experience of viewing the trial.

Such support is necessary now, and will impact the future. One formerly abducted young lady who returned with children from captivity once remarked in a Justice Tafakari (a peace and justice dialogue) in Gulu that:

“It is important for all different actors and the communities to know that if the children with which we returned from captivity are not properly rehabilitated, then … bigger conflicts still lie ahead!”

Although much work remains to be done, through various interventions under their respective mandates, the ICC and TFV have taken steps to directly address trauma and be an active part in the healing process, and the many miniature rehabilitative efforts being made by different civil society organizations and informal community groups cannot go without acknowledgement. The journey is long, but it is one that is possible.