In some ways being a Court reporter is like being a concert pianist. The intensity. The focus. The keys and the harmonious combinations they create. Living in a world of sounds. You may even think it looks like I am playing the piano as I work.

But unlike a pianist, my work is also legal. Full of human drama, with stories of those who suffered some of the world's most serious crimes. The Courtroom drama: Arguments put forward from all sides, from all perspectives. The legal terminology, a complicated and relatively new legal system, and the procedural issues that come with it.

But unlike a pianist, my work is also legal. Full of human drama, with stories of those who suffered some of the world's most serious crimes. The Courtroom drama: Arguments put forward from all sides, from all perspectives. The legal terminology, a complicated and relatively new legal system, and the procedural issues that come with it.

To me, these transcripts are important in 3 ways:

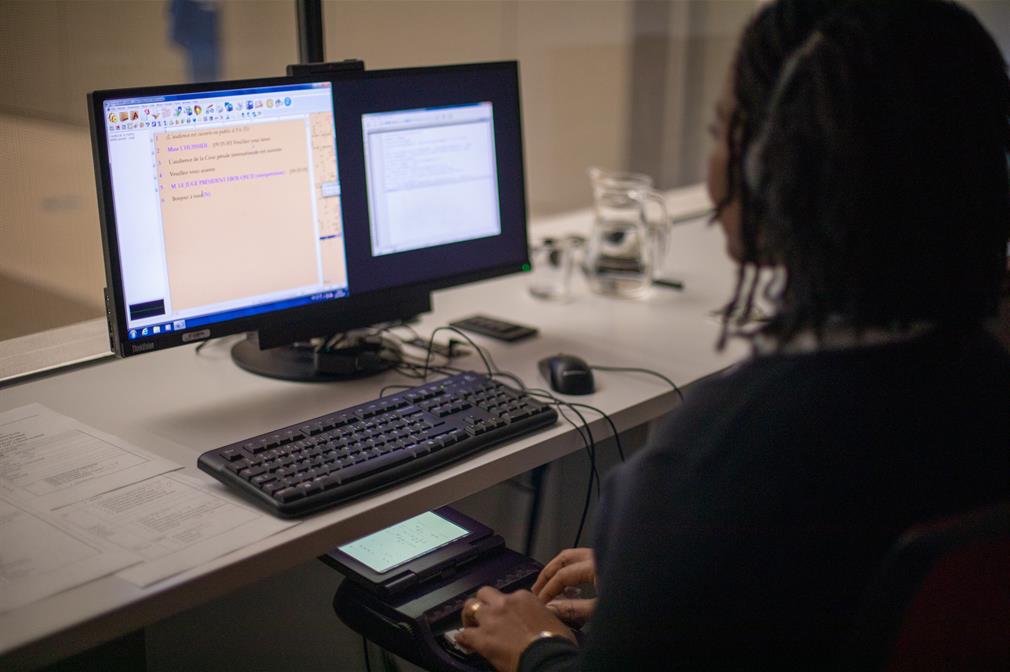

1. They are followed by everyone in the Courtroom in real time. Not only are people listening to the interpreters on their headphones, my transcripts come up live on their screens – so can be referred to – objected to – quoted – all during the course of the same hearing, all live.

2. They are official records. These are used by people in the Courtroom but also by journalists, researchers, students, artists, activists and, perhaps a hundred years from now, historians – anyone who wants to check back on the specifics of a case or see the ins and outs of how a legal precedent was set.

3. They help set the record straight. For the victims and their families, this is their story. The formally recognised account of what they experienced. A way to acknowledge both their suffering and survival as well as their right to be heard. Victims in Uganda, for example, have asked for ICC transcripts to be made into a book they can give to their children. As they watched the proceedings live and saw this written record being created, they said: "This is history in the making. The history of us."

I can honestly say I love the challenge of my work. To do it, you do need to understand the legal terms and system, but you don't need a law degree. Some of our colleagues always knew they wanted to do this. Others, not at all. Our colleague Grace was a biochemistry major and accidentally fell in love with stenography. I studied archaeology. One day I took what I thought would be "computer" training, and it was a stenographer training course. I was alone in my beginner's class. After a few months, I had to join another group for building speed. It was so intense, the others all dropped out, and I was asked to join a much more advanced class. It was terrible – way too fast for me. So I quit. But later, back at home, I thought: "Wait, they are no better than me, if they can do it, I can too." So I started again, training long hours every day, determined to be the fastest and the best.

It's an obsession of sorts, a passion. There is an adrenaline rush to capture every word at every second that goes by, before they disappear into thin air. But there is control: I am always calm, prepared. I often close my eyes, listen, look inward and produce. It's a way to challenge yourself to the extreme, get your heart racing, and do something worthwhile.

There are usually 8 stenographers at the ICC, 4 for French and 4 for English. During a hearing, I sit alone in a booth at the side of the Courtroom, following the proceedings and typing the transcripts live. My counterpart back in the office follows my live version to check and make any corrections before the document is logged as the official record. If the language spoken in the Courtroom is not French, I listen to the French-language interpreter and the transcripts are based on their words. If they make a mistake, I cannot correct it in the transcript: the mistake is part of the official record. Someone in the Courtroom would have to point out the mistake and state the correction during a hearing, and thus be rectified in that new part of the transcript. So everyone is watching, making sure each word I capture is correct, so we can document the proceedings. After all, the transcripts, like the proceedings themselves, aim to get at the truth.

Some days are hard: Often, sometimes day after day, you will hear the testimony of someone who lost everything. At least once in your career, it just gets to you. Since you are alone in your booth next to the Courtroom (instead of inside the Courtroom, like in some other tribunals), you can let the tears just stream down as you type. That's when you know you need a break - take time off, rejuvenate, know that your work is part of someone else's healing process, then dive back into work. But most days, you are just focused on the job: capturing the sounds, the words, the official written record.

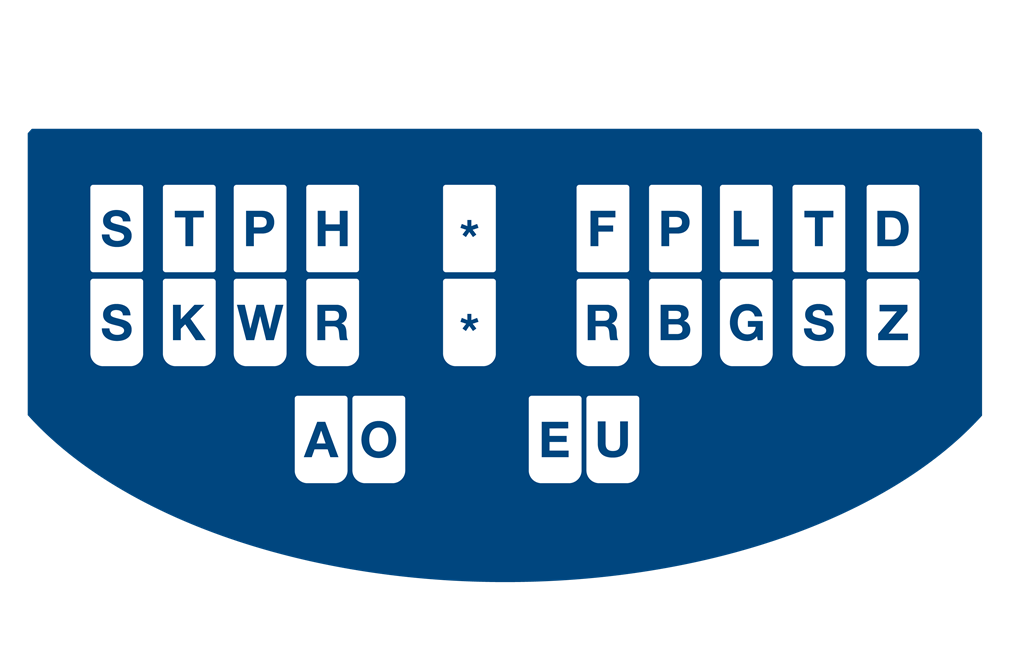

You do so in shorthand. Systems vary, especially between English and French, and we make transcripts in each. The keyboards are different, too, though none of the keyboards have letters. There is no need – you know the keyboard so well, you type by reflex. In the English version, consonants are at the top, vowels at the bottom. Hit the right combination of sounds and voila! You form the sounds that make up the words. The actual keyboard doesn't have letters, you just know the right combinations to make the sounds. But if there were letters on the keyboard, it would look something like this:

And in French, it looks something more like this:

In both systems, you capture phonetic sounds as they are spoken, so you capture each syllable in real time. The flow of creating words is from left to right. So, a sound that begins the syllable I make with the left-hand keys, and close the syllable on the right.

It looks like a secret code at first, but anyone can learn. You would need to study shorthand theory for only a few months, but it takes about 3 years of training and experience to build up to the acceptable speed - 200 words per minute, including complex legal terms - and guarantee the accuracy required to work on ICC proceedings.

And it is more than recording sounds. Your own comprehension of those sounds is key. A robot simply can't do the job. I like to compare it to the autocorrect on your phone. Has it ever messed up one of your texts? Of course. Same would happen here. There are unfamiliar names from across the globe, complex legal concepts, legal terms, a focus on different topics, crimes and arguments each day in a case, locations specific to the charges against the suspect, local cultural references, people speaking with different accents, and so on... it takes a lot of homework and preparation to be ready for each day of a hearing, to anticipate what might be said and to understand it before it is even uttered... there is no way a computer or software can capture all this with 100% accuracy... not even close.

Not that we don't use software – we do. Our software actually translates our shorthand into words. Without it, only those who could read shorthand would be able to understand the transcripts. But for the software to work, you have to pre-feed it what you want it to know. You tell it how to read what you write. Each day we add new names, new terms, anything we can anticipate that might be said the following day in Court. No doubt software is an essential tool. But at the end of the day, a person needs to do this job. For transcripts, humans win out every time.

Sort of like music. A lot like art. Just more legal. And official. The official records of the Court.